[ad_1]

Sure sorts of tansu, made to be moved round incessantly, would generally have their joinery strengthened with nook braces and strapping {hardware}. Tansu {hardware} was generally constituted of iron, however many smaller items used copper. I selected copper for the tansu in my article (“Conventional Tansu,” p. 52). Iron {hardware} could be bought within the States, however copper {hardware} is troublesome to search out outdoors Japan, and I made a decision to make my very own. Though that is Grasp Class, I wouldn’t name myself a grasp of this–only a man who fumbles round and finds methods to unravel for x. As soon as I discovered the trail, nevertheless, the processes have been surprisingly easy and the outcomes have been extraordinarily gratifying.

Sure sorts of tansu, made to be moved round incessantly, would generally have their joinery strengthened with nook braces and strapping {hardware}. Tansu {hardware} was generally constituted of iron, however many smaller items used copper. I selected copper for the tansu in my article (“Conventional Tansu,” p. 52). Iron {hardware} could be bought within the States, however copper {hardware} is troublesome to search out outdoors Japan, and I made a decision to make my very own. Though that is Grasp Class, I wouldn’t name myself a grasp of this–only a man who fumbles round and finds methods to unravel for x. As soon as I discovered the trail, nevertheless, the processes have been surprisingly easy and the outcomes have been extraordinarily gratifying.

On this article:

Len Cullum has the blanks for his tansu {hardware} minimize with a water jet.

Fortunately, he shared his information with us so you may ship

them to a fabricator and do the identical.

Proper-click right here to obtain the zip file containing DXF information

Which end?

My early conferences with tansu have been with antiques, and to me there was one thing simply implausible about their put on and injury and patina. It gave them a heat and life that captivated me. A lot later, on a visit to Japan, I noticed a model new tansu, and it left me a bit chilly. Whereas the craftsmanship was in each method beautiful, it simply didn’t converse to me in the identical method these outdated, well-used ones did, and it occurred to me that my love of tansu had simply as a lot to do with their entropy because it did with their proportions and designs. That’s why I selected to make use of uncooked copper for the {hardware} on this piece. Historically, it could be handled with a coat of urushi lacquer after which heated to provide a shiny brown end. I left mine unfinished to permit the visible getting older of the piece to proceed unabated. If my consumer hadn’t requested an oil end, I’d have left the wooden on this piece untreated as effectively.

Strapwork

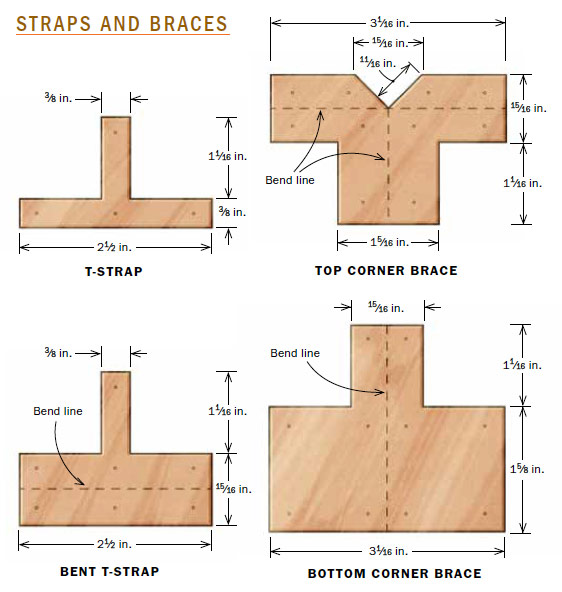

I used 22-gauge copper sheet to make all of the nook braces and strapping. Whereas I initially deliberate to make use of snips and minimize the blanks out by hand, I actually struggled to maintain the copper from curling, and as soon as it did curl, to get it flat once more. My resolution was to have the blanks minimize with a water jet. It was pricey—about $200—however I justified the associated fee by having 4 12-in. by 18-in. sheets stacked and minimize directly; this offered me with sufficient elements for half a dozen comparable tansu cupboards.

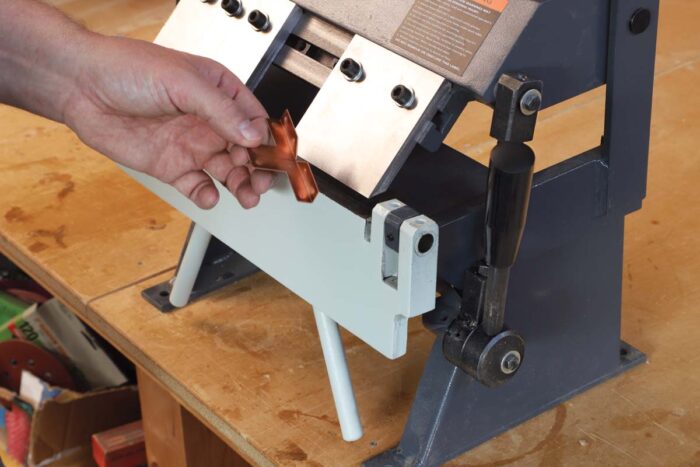

As soon as the blanks have been minimize, the processing was fairly easy: Drill the nail holes, kind the nook items utilizing a small pan brake, then file and sand the sides easy. Lastly, polish away the tarnish left by the chopping course of.

Drill for nails. Plates and braces are affixed with escutcheon nails. With the protecting plastic sheet nonetheless on the copper clean, lay out the holes and mark every one with a nail punch. Then bore the holes on the drill press with a hardwood block for backup.

|

|

Abrade the bracing. After drilling, take away the plastic and flat-sand the {hardware} with 400-grit paper on an MDF sanding block. Then file the sides barely spherical.

Bending tansu {hardware} by hand

|

|

For those who’re utilizing a hand seamer to make the bends, place the workpiece so the bend line is simply shy of the seamer’s jaw, and bend upward. Attempt marking and bending take a look at items beforehand to get a really feel for the method.

The hand brake creates a rounded nook. To sq. it off a bit, clamp the workpiece to a square-edged anvil and form it utilizing a hardwood caul and a hammer.

Clear the copper. Earlier than putting in the {hardware}, polish its surfaces.

Nail it. Cullum used 1⁄4-in.-long #18 strong copper escutcheon pins to nail on the copper {hardware}. Strong copper pins are offered in Japan, however are arduous to come back by in the USA. Brass pins, simpler to search out, look totally different initially, however match the copper extra carefully as they patina over time.

Conventional tansu-style warabite drawer pulls

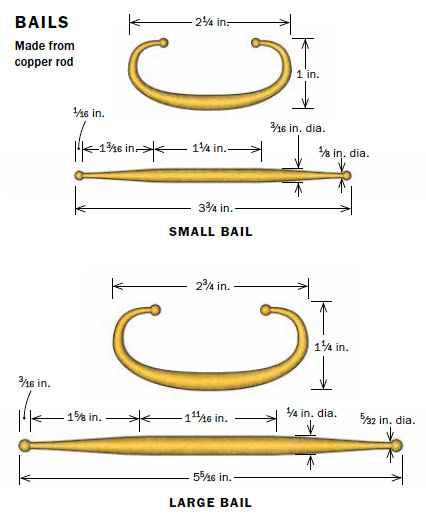

Drawers on conventional tansu usually have bails made in a method referred to as warabite, for its resemblance to the curling form of bracken shoots. My unique plan was to hot-forge warabite bails from copper rod with a hammer. However after a lot apply and plenty of makes an attempt, it turned clear I’d want a number of extra months of apply earlier than I might strategy the consistency I would want to make all of them match. So I attempted a special route: At a strip sander, I sanded rod inventory to a double-tapered form, then bent it over a kind.

Drawers on conventional tansu usually have bails made in a method referred to as warabite, for its resemblance to the curling form of bracken shoots. My unique plan was to hot-forge warabite bails from copper rod with a hammer. However after a lot apply and plenty of makes an attempt, it turned clear I’d want a number of extra months of apply earlier than I might strategy the consistency I would want to make all of them match. So I attempted a special route: At a strip sander, I sanded rod inventory to a double-tapered form, then bent it over a kind.

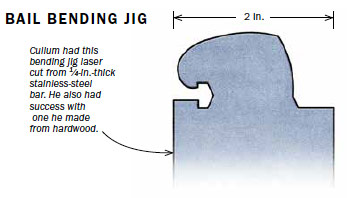

I began by measuring some vintage handles and making a wood bending jig. As a result of I used to be eager about working copper the identical method I labored metal, I heated up a copper rod and tried it out. The jig labored effectively, however the sizzling copper burned into the wooden far more shortly and deeply than I had anticipated. Until I wished to remake the jig repeatedly, I’d want a special resolution. So I made a decision to have a bending kind laser minimize from a bar of 1⁄4-in.-thick chrome steel. This labored nice, however quickly after, I noticed that the copper labored properly chilly, so I might have used the wooden kind in any case. (On the upside, I now have a bending jig that may outlast me.)

For the smaller drawers, I made bails from lengths of three⁄16-in.-dia. copper rod; for the massive backside drawer, I used 1⁄4-in.-dia. rod. After chopping the rod to size, I made reference marks for shaping. Then, utilizing a 1-in.-wide belt on the strip sander, I roughed out the double taper, incessantly checking the slender diameter with calipers and leaving a knob at every finish of the rod. As soon as all of the tapers have been formed, I cleaned up the knobs on the strip sander. I hand-sanded the bails to 400-grit, and polished them with maroon and grey abrasive pads.

Tapering copper rod. To make the bail, Cullum rotates a size of copper rod towards the strip sander. He creates two tapers with a full-diameter part between them. |

Around the knob. Having left a small part full-size at both finish of the tapered bail clean, Cullum twists the rod to around the ends. |

Abrasive cleanup. Easy the bail’s surfaces by handsanding with 400-grit paper, and observe that with Scotch-Brite pads. |

Bending and fixing the bails

Then it was off to the bending jig. Hook one knob into the opening and bend the bar over the curve; reverse and repeat. Whereas 3⁄16-in. bails cold-formed properly, the 1⁄4-in. ones have been a bit too stiff to bend tightly to the shape, in order that they wanted to be annealed to make them extra ductile. To anneal them, I used a propane torch, heated them to cherry pink, after which quenched them in water. Quenching metal hardens it, quenching copper makes it softer. After that they bent across the jig fantastically.

Then it was off to the bending jig. Hook one knob into the opening and bend the bar over the curve; reverse and repeat. Whereas 3⁄16-in. bails cold-formed properly, the 1⁄4-in. ones have been a bit too stiff to bend tightly to the shape, in order that they wanted to be annealed to make them extra ductile. To anneal them, I used a propane torch, heated them to cherry pink, after which quenched them in water. Quenching metal hardens it, quenching copper makes it softer. After that they bent across the jig fantastically.

Tansu bails are historically hooked up to the drawer entrance with a metallic strip formed like a cotter pin. The pins are pushed via holes within the drawer face, opened, laid flat, and their pointed ideas are pushed into the again of the drawer face, not in contrast to a clinch nail. Getting access to strong bronze cotter pins (shoutout to Stoneway {Hardware} in Seattle), I made a decision to make use of these as an alternative of constructing copper ones.

Cotter pins sometimes have a teardrop-shaped gap; I made the holes a bit rounder by inserting a bit of spherical bar after which fastidiously pinching the pin round it with needle-nose pliers. I additionally sharpened the tricks to make them simpler to hammer in. Earlier than the ultimate set up there was loads of dry-fitting, checking the motion of the pull, after which a number of small tweaks to get them to swing freely. I made all these changes utilizing a dummy drawer entrance drilled for the cotter pins.

Cotter pins sometimes have a teardrop-shaped gap; I made the holes a bit rounder by inserting a bit of spherical bar after which fastidiously pinching the pin round it with needle-nose pliers. I additionally sharpened the tricks to make them simpler to hammer in. Earlier than the ultimate set up there was loads of dry-fitting, checking the motion of the pull, after which a number of small tweaks to get them to swing freely. I made all these changes utilizing a dummy drawer entrance drilled for the cotter pins.

For the small spherical escutcheons, I once more went to the {hardware} aisle and located strong copper rivet burrs. They wanted to be dome formed to work as escutcheons, so I used a dapping block and hammered them into form.

After putting in the entire pulls, I hammered a single small nail into the drawer entrance the place the pull would contact the drawer face. This nail, referred to as an atari, protects the wooden from being dented by the pull’s dropping.

|

|

Hand bent bails. The tapered copper bars bend easily and simply over the jig, but are loads stiff sufficient to carry their form. Due to copper’s softness, it’s key to verify the jig’s floor is easy so it doesn’t go away texture on the completed bail.

|

|

The bail will get completed and stuck. After finishing the bend, Cullum polishes the bail, then provides at every finish a cotter pin with a custom-made copper washer. He offers the washers their domed form with a dapping block.

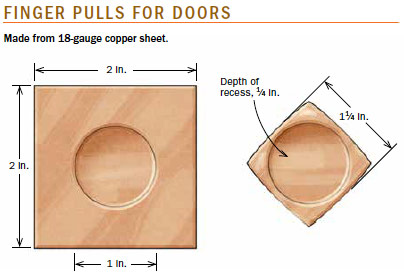

Finger pulls for the doorways

Making the recessed door pulls concerned a bit trial and error (a specialty of mine). In my try to make a low-tech punch press, I began out utilizing totally different sizes and sorts of wooden dowels paired with drilled wooden blocks, and I attempted totally different hammering strategies. However the wooden simply couldn’t face up to the folding forces of the copper, and the method left creases within the sides of each the copper and the dowels. Then I arrived at a tooling resolution that labored fantastically.

Making the recessed door pulls concerned a bit trial and error (a specialty of mine). In my try to make a low-tech punch press, I began out utilizing totally different sizes and sorts of wooden dowels paired with drilled wooden blocks, and I attempted totally different hammering strategies. However the wooden simply couldn’t face up to the folding forces of the copper, and the method left creases within the sides of each the copper and the dowels. Then I arrived at a tooling resolution that labored fantastically.

It began with annealing 2-in. squares of copper to get them mushy sufficient to stretch whereas forming. With out annealing they only crumple and tear. Subsequent I stacked two 1⁄8-in.-thick, 1-in.-dia. washers on an anvil, waxed either side of the copper and the tip of a 3⁄4-in. socket, after which gave the socket a few good whacks. As soon as the socket reached the anvil, I eliminated the copper, fastidiously tapped out the wrinkles on the higher floor, minimize it to form with snips, and sanded over the sides to present it a barely domed look. Lastly, I drilled two nail holes within the partitions of the recess and polished the pull with abrasive pads.

|

|

Selfmade punch press. With a sacrificial socket wrench socket and a few large washers, Cullum devised a machine to emboss copper sheet for finger pulls. After pounding, he fastidiously faucets out the wrinkles within the skirt across the recess.

Candy transition. After tapping out the wrinkles, Cullum trims the skirt with snips, smooths the sides with a file and abrasives, then polishes all surfaces. He additionally drills two small holes for nails within the facet wall of the recess.

Making this {hardware} was removed from price efficient or environment friendly, however it was value it. I acquired what I wished, and I realized loads that may inform future tasks.

Len Cullum works wooden in Seattle, Wash.

Join eletters as we speak and get the most recent strategies and how-to from Positive Woodworking, plus particular presents.

Obtain FREE PDF

if you enter your e mail handle beneath.

[ad_2]